The Manhattan Project began in 1942. At that time, research was being conducted at universities across the country into questions of atomic energy. Under the direction of the Army and General Leslie R. Groves, the project consolidated and organized this research. By the end of 1942, project leaders realized that three new sites would have to be built: uranium enrichment facilities at Oak Ridge, Tennessee; plutonium production facilities at Hanford, Washington; and a laboratory specializing in the actual construction of the bomb. This laboratory, also called Project Y, would bring together scientists and engineers to construct and test the first atomic bomb.

As members of the Manhattan Project searched for places to build the three sites, they had a number of guidelines. For Project Y especially, secrecy was paramount, and so isolation was the first requirement. The location also needed to be large, sparsely populated, warm enough to continue work year round, and far from each coast. The new laboratory, however, could not be completely isolated. It would depend on nearby power and water sources, as well as established roads and buildings to transport materials and house the early personnel. As a result, project leaders knew they would have to take over inhabited sites to best suit the needs of their project.

After a number of site visits and discussions with men such as the laboratory’s director J. Robert Oppenheimer, General Groves decided that the laboratory would be centered near Otowi, New Mexico, at a boys’ school called the Los Alamos Ranch School. According to physicist Edwin McMillan, “Soon as Groves saw it, Groves said, ‘This is it.’”

The Manhattan Project in Northern New Mexico

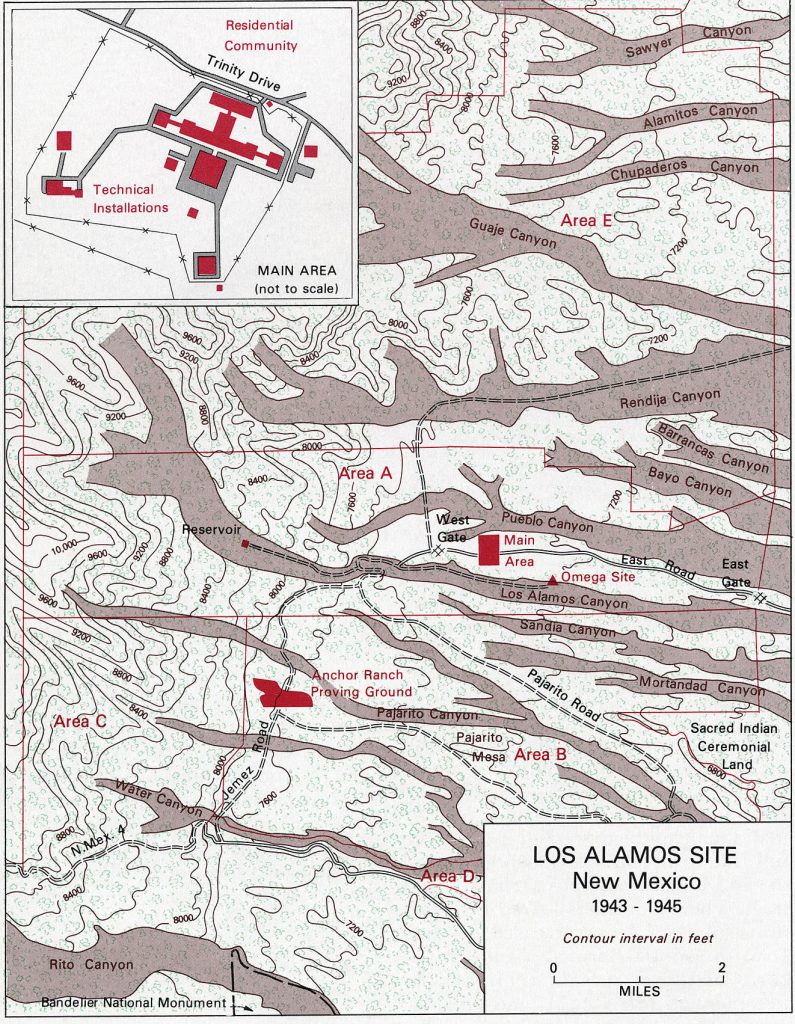

In order to secure the land they wanted for their new laboratory, the leaders of the Manhattan Project had to buy up about 50,000 acres. While most of the land already belonged to the government, there were also two dozen homesteaders and two larger properties, the Los Alamos Ranch School and the Anchor Ranch.

In order to secure the land they wanted for their new laboratory, the leaders of the Manhattan Project had to buy up about 50,000 acres. While most of the land already belonged to the government, there were also two dozen homesteaders and two larger properties, the Los Alamos Ranch School and the Anchor Ranch.

On March 22, 1943, Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson sent a letter to the Secretary of Agriculture, writing that it was a matter of “military necessity” to acquire about 45,000 acres under the jurisdiction of the Forest Service to establish a “demolition range” at Los Alamos. On April 8, 1943, the Secretary of Agriculture granted the War Department use of the land, providing that certain conditions of fire prevention and protection be enforced. The large amount of federally owned land in the area was one of the advantages of the site near Otowi, saving the Army time and money in its race to build the atomic bomb.

Another major advantage of the location was the Los Alamos Ranch School and its collection of buildings. Started in 1917 by Detroit entrepreneur Ashley Pond, the school aimed to produce strong young men through a combination of rigorous outdoor living and classical education. On December 7, 1942, one year after the attack on Pearl Harbor, a letter arrived from Henry Stimson. Addressed to A. J. Connell, the school’s director, the letter announced that the U.S. Army was taking over the school’s property in “the interests of the United States in the prosecution of the war.” Stirling Auchincloss Colgate, who was a student at the school at the time, said that Connell “was totally broken up by having his life’s work moved. But he made us all understand how extremely serious this was without knowing himself.”

As the students hurried to finish their studies, lawyers hired by the school negotiated with the government for the sale of the land. In exchange for the fifty-four buildings and 470 acres, the school received $350,000. These buildings would house the early arrivals to Los Alamos. The nearby Anchor Ranch consisted of four houses and a small barn sitting on a tract of 320 acres. Its owners also negotiated directly with the government, and the property was sold for $25,000.

Acquiring the land from the homesteaders was a different story, and the government and homesteaders each give different accounts of the process.

The official Manhattan District History—written under the direction of Gavin Hadden, the project’s official historian—relates the process by which the land was acquired. Grazing permits from the area were withdrawn after direct negotiation, and payments were given of between $20 and $30 for each head of stock that had grazed there. The privately owned land was either purchased after direct negotiation or condemned under the Second War Powers Act. In the cases where the land was condemned, Declaration of Taking proceedings were initiated to speed up the process, which allowed the government to immediately take the land without direct negotiation with its owners. Appraisals were made based mainly on prices of comparable land, but also on factors such as location, soil type, and topography. There were a few objections to the prices offered by the government—principally by homesteaders Elfego Gomez, Martin Lujan, and Ernesto and Adolfo Montoya—but most parties settled without any problems.

The official Manhattan District History—written under the direction of Gavin Hadden, the project’s official historian—relates the process by which the land was acquired. Grazing permits from the area were withdrawn after direct negotiation, and payments were given of between $20 and $30 for each head of stock that had grazed there. The privately owned land was either purchased after direct negotiation or condemned under the Second War Powers Act. In the cases where the land was condemned, Declaration of Taking proceedings were initiated to speed up the process, which allowed the government to immediately take the land without direct negotiation with its owners. Appraisals were made based mainly on prices of comparable land, but also on factors such as location, soil type, and topography. There were a few objections to the prices offered by the government—principally by homesteaders Elfego Gomez, Martin Lujan, and Ernesto and Adolfo Montoya—but most parties settled without any problems.

The stories of the homesteaders and their descendants, however, illustrate the fear and uncertainty in these proceedings. Rosario Martinez Fiorillo, whose ancestors built the Romero Cabin on the Pajarito Plateau, described the homesteaders’ reactions to the Army taking over their land and the difficulty language barriers placed on the process:

They just didn’t go to plant anymore, and they just gave up their land. What else could they do? Because they were frightened by these people in uniform. They came with guns and whatnot, and all of a sudden they came to them and they told them, “Well, you can’t come and plant anymore over here. We’re going to take over. The government wants your land.” Maybe they wrote letters to them in English, but there was nobody to translate these letters for them. They did not understand most of the stuff. They just agreed, “Sí, sí, sí.” What could they do?

In the end, the Army acquired 49,383 acres at a total cost of $424,971. Construction began immediately. The students at the Los Alamos Ranch School could hear the bulldozers before they left the school that winter.

The Legacy of Displacement

While the construction of Los Alamos forced people off of their land, large numbers of Hispano and Native workers from the surrounding areas came back to Los Alamos to work for the project. These workers have been an integral part of the Los Alamos laboratory since its establishment.

Men and women from the Española Valley performed a wide variety of jobs on “The Hill,” including as babysitters, maids, construction workers, janitors, and technicians. There was also, however, discrimination against these local workers. “There were elements of blatant discrimination,” Dimas Chavez remembered. “I can recall going to birthday parties, not that many but a few, where my cake and ice cream was served to me outside. In later years, there were families whose daughters were not allowed to date Mexican-Americans. Thankfully there was not that much, but it was there.”

Even though they were invited behind the walls and into the “secret city,” a distance was often maintained between the scientists and these workers. As historian Peter Bacon Hales writes in Atomic Spaces: Living on the Manhattan Project, “Where they differed from other people of color on other [Manhattan Project] sites was in their intimate proximity to the lives of the scientific families who would eventually become heroes. Too close to be threatening, they became exotic; their differentness made them objects of romance…”

The Los Alamos laboratory—and World War II more generally—forever changed the peoples of the Española Valley. The temporary wartime site turned into a national laboratory, now one of the largest employers in northern New Mexico. As a result, the people of local Pueblos were drawn out of their traditional work, moving away from subsistence agriculture and into an economy that depended on the outside world.

Viewpoints differ about the laboratory and its legacies. Lydia Martinez and others described how the lab invigorated the economy of the area. “People in the area were very poor at that time. There was not a lot of work. Most people did farming. But once the lab came in, everybody started prospering. You saw everybody improving their homes. There were vehicles, and people buying condos here and there. It was a good thing for us living in the Valley.”

Others, however, cite negative health and environmental impacts of the Laboratory and resent its economic influence on the area. “Los Alamos, you can’t live with it and you can’t live without it,” one man told oral historian Peter Malmgren. The relationship between Los Alamos and its surrounding communities has offered mutual benefits over the past seven decades, but many issues still remain.

Years after the Manhattan Project displaced the homesteaders from their land on the Pajarito Plateau, their descendants petitioned the federal government for the money owed to their ancestors. While the Los Alamos Ranch school was paid about $225 per acre and the Anchor Ranch was paid about $43 per acre, the homesteaders were often paid as little as $7 an acre. Some landowners never received their payments. In 2004, Congress established a $10 million fund to pay back the families of the homesteaders. While the government denied taking the land illegally, it did acknowledge that these Hispano homesteaders were paid less than other property owners, and that many did not have legal representation.

Interpreting Manhattan Project History

On November 10, 2015, the National Park Service (NPS) and the Department of Energy signed an agreement that officially established the Manhattan Project National Historical Park with units at Los Alamos, NM; Oak Ridge, TN; and Hanford, WA. The agreement provided a division of roles in managing the new park. The NPS is the “storyteller” and interprets the Manhattan Project history while DOE maintains its properties that are part of the new park.

After convening meetings with scholars and the public, NPS published four major interpretive themes for the park. The first theme highlights displacement: “The “secret cities” created by the Manhattan Project, and the sacrifice and displacement connected to them, exemplified this massive wartime effort demonstrating remarkable opportunities to reflect on the extraordinary lengths to which people and nations go to protect their futures.”

For more information about visiting the Manhattan Project National Historical Park, please click here.